سه شنبه, ۲۳ بهمن, ۱۴۰۳ / 11 February, 2025

بدن

مسیر ترجمه: انگلیسی - فارسی

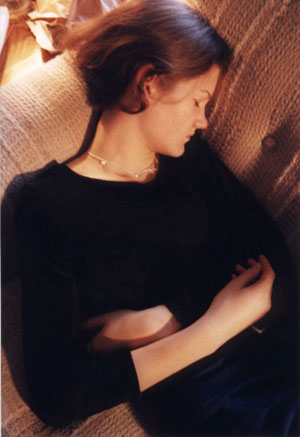

هرچند چنین تصور میشود که برای انسان چیزی ملموستر و عادیتر از بدن او، واقعیتی عینیتر و فراتاریخیتر از واقعیتهای کالبدشناختی، و هیچ نمودی از آزادی بدیهیتر و مدرنتر از آزادی بدن نیست؛ با اینحال، غالب این تصورات طی چهل سال اخیر در فرانسه آماج انتقادهای شدید قرار گرفت و اساساً به زیر سؤال رفت. این پرسش و دغدغه نسبت به بدن علاقه زیادی ایجاد کرده بود.

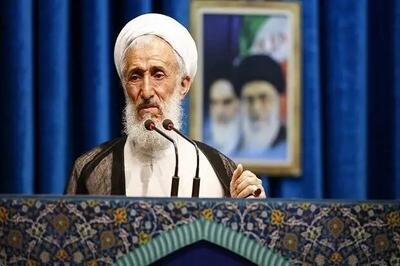

به یک معنا، «بدن» به عنوان مهمترین مفهوم انتقادی سیر اندیشه در فرانسۀ بعد از 1968، جایگزین «وجود» (being)، «ساختار» (structure) و «نشانه» (sign) شد. امروزه این تغییر نگرش و رویکرد نظری نسبت به بدن حوزه علاقه بسیاری از افراد را تشکیل میدهد. میشل فوکو ـ به خصوص در قلمروی انگلیسی زبان ـ بیش از همه در این تغییر نگرش دست داشته است. در یکی از آثار فوکو راجع به تاریخ جنون و نهادهای مراقبتی، بدن ابژهای است که تحت کنترل شدید قرار گرفته به عرصه بروز و ظهور نمادها بدل میشود. فوکو در متنی به یاد ماندنی در ابتدای مراقبت و تنبیه (Discipline and Punish) صحنه شکنجه و اعدام دامیَن قرن هیجدهمی که قصد جان شاه را کرده بود، توصیف میکند. مجازاتهای هولناکی که بر بدن دامیَن وارد آمد، نه اعمالی ظالمانه و سرخود، که نمایش نظاممند انتقام شاه از قاتل احتمالیاش را نشان میدهد. در این مثال و مثالهای فراوان دیگر، بدن جوهر انعطافپذیری است که وادار به انطباق با اعمال خاصی شده است. «بدن مستقیماً درگیر میدان سیاسی است؛ روابط قدرت کنترلی بلافصل بر بدن دارند؛ بدن را میخرند، بر آن نشانه میزنند، تربیتش میکنند، گوشمالیاش میدهند، و آن را ملزم به انجام وظایف، اجرای مناسک، و تولید نشانه مینمایند.» اثر فوکو بدنی را به نمایش میگذارد که در جریان است، بدنی که در طول تاریخ اَشکال عجیب و شگفتانگیزی به خود گرفته است. چنین نیست که بدن محمل راکد و خنثایی برای روح باشد، بلکه دائماً به واسطه مجموعهای از گفتمانها، مراقبتها، و رویههای فیزیکی، شکل گرفته و تغییر شکل یافته است. با وجود آنکه شکنجه و سایر آزارهای بدنی در دوره روشنگری رو به زوال گذاشت، بدن به عنوان هدف نهایی قدرت و معنا باقی ماند. زندانها نسبت به توانبخشی به مجرم از طریق تأثیرگذاری بر ذهن و روح او توجه بیشتری را ملزوم داشتند؛ با اینحال چنانکه فوکو تأکید میکند، «روح معلول و ابزار کالبدشناسی سیاسی است؛ روح زندان بدن است.» درس فوکو به ما آن است که در یک میدان سیاسی علیرغم ایدئولوژیهای مبتنی بر بشردوستی و عطوفت، بدن همچنان از بیشترین اهمیت برخوردار است.

Although it would seem that no object is more banal and familiar to the individual subject than his or her body, no reality more objective and transhistorical than the givens of anatomy, and no expression of freedom more self-evident and modern than liberation of the body, most of these assumptions have been called into question and subjected to a radical critique during the last forty years in France. This questioning and theoretical preoccupation with of the body has attracted great interest.

In some sense, “the body” replaced “being,” “structure,” and the “sign” as the most important critical term in post-1968 French thought. The author most responsible for this change, especially in the English-speaking world, was Michel Foucault. In his work on the history of madness and disciplinary institutions, the body emerges as an object of intense control and symbolic investments. In a memorable passage at the beginning of Discipline and Punish, Foucault describes the torture and execution ofدthe eighteenth-century regicide Damiens. The terrible punishments inflicted on Damien’s body were not gratuitous acts of cruelty but rather a systematic display of the king’s vengeance on his would-be assassin. In this and many other instances, the body is a malleable substance, made to conform to specific tasks. “The body is directly involved in a political field; power relations have an immediate hold upon it; they invest it, mark it, train it, torture it, force it to carry out tasks, to perform ceremonies, to emit signs.” Foucault’s work reveals a body in flux, one that has taken strange and surprising forms throughout history. Instead of being an inert, neutral dwelling place for the soul, it has constantly been shaped and distorted by a host of discourses, disciplines, and physical practices. Although torture and other abuses of the body receded during the Enlightenment, the body remained the ultimate objective of power and signification. Prisons were more concerned with rehabilitating the criminal by appeal to his mind and soul; however, as Foucault insists, “The soul is the effect and instrument of a political anatomy; the soul is the prison of the body.” Foucault’s lesson is that in the political field, despite an ideology of kindness and humaneness, the body is still what matters most.

متیو سنیور، 2004، Encyclopedia of Modern French Thought، منصوره اسدی مقدم، سایت انسان شناسی و فرهنگ، صص 96-100 (http://www.anthropology.ir/node/12365)

ایران مسعود پزشکیان دولت چهاردهم پزشکیان مجلس شورای اسلامی محمدرضا عارف دولت مجلس کابینه دولت چهاردهم اسماعیل هنیه کابینه پزشکیان محمدجواد ظریف

پیاده روی اربعین تهران عراق پلیس تصادف هواشناسی شهرداری تهران سرقت بازنشستگان قتل آموزش و پرورش دستگیری

ایران خودرو خودرو وام قیمت طلا قیمت دلار قیمت خودرو بانک مرکزی برق بازار خودرو بورس بازار سرمایه قیمت سکه

میراث فرهنگی میدان آزادی سینما رهبر انقلاب بیتا فرهی وزارت فرهنگ و ارشاد اسلامی سینمای ایران تلویزیون کتاب تئاتر موسیقی

وزارت علوم تحقیقات و فناوری آزمون

رژیم صهیونیستی غزه روسیه حماس آمریکا فلسطین جنگ غزه اوکراین حزب الله لبنان دونالد ترامپ طوفان الاقصی ترکیه

پرسپولیس فوتبال ذوب آهن لیگ برتر استقلال لیگ برتر ایران المپیک المپیک 2024 پاریس رئال مادرید لیگ برتر فوتبال ایران مهدی تاج باشگاه پرسپولیس

هوش مصنوعی فناوری سامسونگ ایلان ماسک گوگل تلگرام گوشی ستار هاشمی مریخ روزنامه

فشار خون آلزایمر رژیم غذایی مغز دیابت چاقی افسردگی سلامت پوست